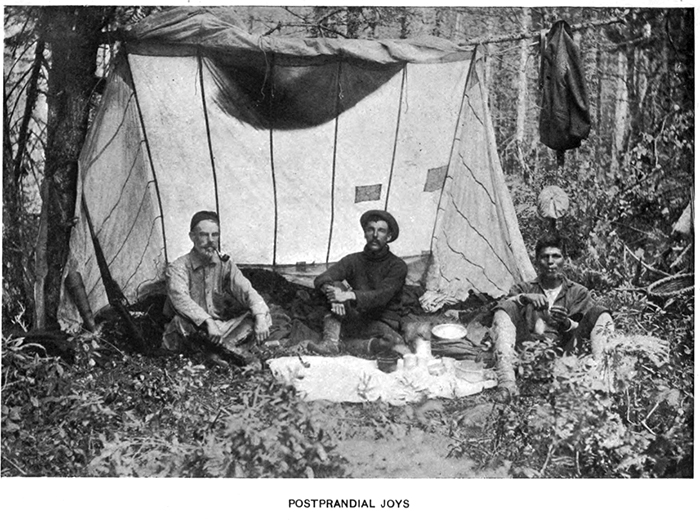

There is a time and place for making temporary camps. When the situation has changed quickly or you just took the moment to seize the day, these tips on sheltering may come in handy from “The Way of the Woods, A Manual for Sportsmen in Northeastern United States and Canada,” by Edward Breck, 1908.

Temporary Camps

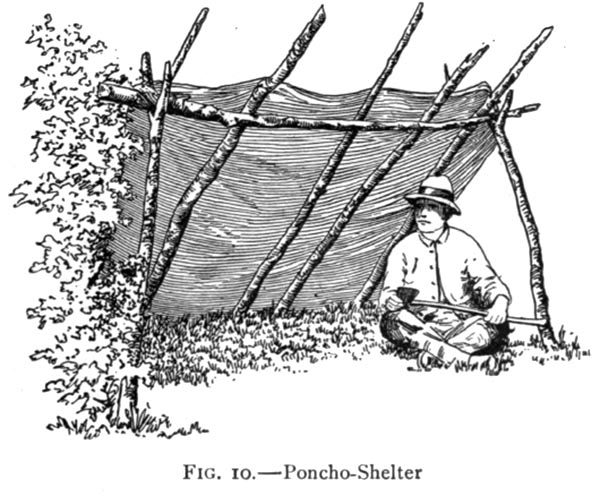

If trips of short duration are undertaken in such light marching order that not even a fly is allowed to burden the kit, it is necessary to knock up some kind of a shelter for the night. In the case of a man with a waterproof sleeping-bag with broad head-flap this need not be more than a wind- or rain-break. If a fly or poncho is taken it is set up on a frame consisting of two forked uprights connected by a middle. Shorter forked poles braced against the side-poles keep the frame stiff and strong.

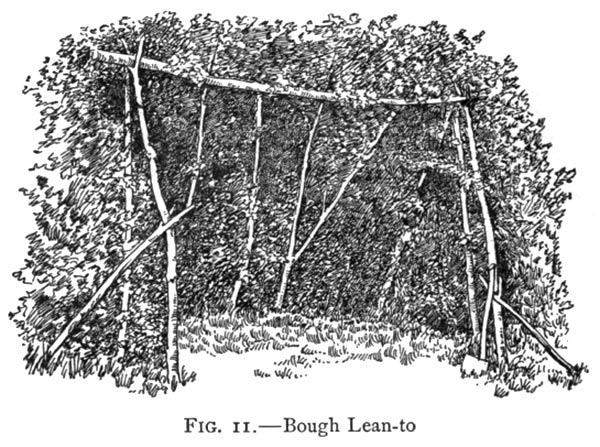

If no artificial shelter is taken a frame similar to the above is made and the space between the two (or three) slanting poles (covered in the lean-to by canvas or poncho) is filled by laying parallel poles closely over it, the whole being then thickly covered with evergreen boughs. If an old, easily peeled hemlock is available, and there is time, cover the poles partially with bark before adding the boughs. Fill in the sides with boughs, or small, thick evergreen trees, and you will have a very comfortable camp, which will be rendered glad and warm by the campfire in front.

A somewhat similar camp, suitable for a single person, is made by felling a hemlock, cutting at about 4 or 5 feet from the ground, leaning the trunk firmly and safely on the stump and filling in one side with the limbs and boughs cut from the side destined for the front.

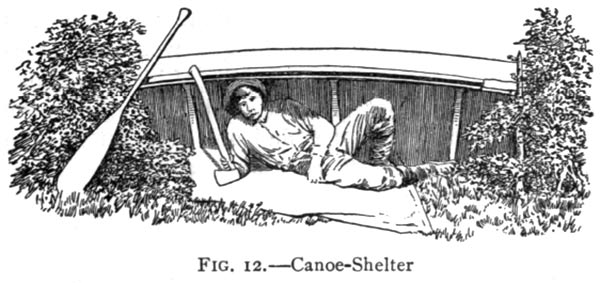

Canoe-Shelter

This consists merely in inverting and bracing the canoe as a shelter for the head, evergreen boughs being banked thickly at the sides to break the wind. If the weather looks at all threatening better take a fly, tarpaulin or poncho; the 4 or 5 extra pounds are likely to repay their transport well.

Persons of any skill and ingenuity can make their own tents, and I strongly recommend them to do so, especially if a good model is obtainable from which to copy. A third or more of the cost will be saved. The very best material is No. I. Egyptian sail-cloth duck, which can be obtained of Harrington, King & Co., 79 Commercial Street, Boston, Mass. It is 31 inches wide and costs $.22 per yard. The other necessary materials are light canvas for binding, grommets, braided clothesline, etc.