After reading this article about moccasins, I find myself wanting a pair. Fortunately, instructions are given on how to make your own in case there isn’t a mall around the corner. I can imagine any squaws that read this will be madder than a Wampus Cat in a rainstorm that the author thought they didn’t have “mechanical skill nor the appliances” to make good moccasins. This description is taken from “Camping and camp outfits. A manual of instruction for young and old sportsmen” by G.O. Shields, 1890.

How to make moccasins

For dry weather, and dry land, winter or summer, in the woods, in the mountains, or on the plains, the most comfortable and serviceable of all foot-gear is a heavy buckskin moccasin. The white man has never been able to excel the native Indian in this one matter. The moccasin is the most natural, rational, perfect piece of foot-wear ever worn by human beings. Not even the old Greek sandal was so perfect, for it protected only the sole of the foot, while the moccasin protects the whole of it, and in so graceful and grateful a manner that any man who puts on a pair of them for the first time feels like calling down the blessings of heaven on the soul of the ancient red man, whoever he was, that invented them.

When a man whose feet have been cased up in tight-fitting leather boots or shoes, with heavy, awkward, cumbersome soles, and unnatural and ungraceful heels on them, to obstruct his movements at every step, gets out into the woods, and puts on a pair of moccasins for the first time, he feels like the school-boy who has been shut up within brick walls for six months with his books, and is turned out on his uncle’s farm for his summer vacation; he feels like a race-horse that has been stabled through a long winter, and in the spring is turned out in a field of green clover; he feels like a bird-dog that has been housed up in his city kennel all summer, and, in the cool, bright autumn days, is turned loose in the country among the quails or prairie chickens. When a man, I say, whose feet have been pinched and whose corns have been cultivated with leather boots or shoes for years, gets out and gets his first pair of moccasins on, he wants to run, leap, sing, dance, shout, whistle — he wants to do anything that will give vent to his joyous feelings. He would shake hands then with his worst enemy, if he were there, and slap him on the back; he would buy his wife a seal-skin sack; he would hug his grandmother.

However, there are many sportsmen who imagine they would not like moccasins, and some few who have tried them and are sure they don’t like them; but those who have worn them most like them best. For fall or winter hunting, they should be made large enough to admit of two pairs of socks being worn; and if rocks hurt the bottoms of your feet, put a pair of sole-leather insoles in your moccasins. If the cords in the calves of your legs get sore from walking, this is not the fault of the moccasins; it is the fault of the useless and unnatural high heels you have been wearing on your boots or shoes, and it will pass away after a day or two. Then you will find that you can walk all day in moccasins, and be less tired at night than if you had walked two hours in any other foot-gear. You will find that you can move more quietly than in any other boot or shoe; that you suffer less from cold feet, and that the buckskin clings to rocks and logs better than rubber or leather. Even if you don’t wear moccasins, you should have a pair with you on every camping-trip, to put on at night when you come in from your day’s tramp. You will find them restful and refreshing — an excellent camp-slipper. Don’t depend on buying them from the Indians, or even of Indian make. The squaws have not the mechanical skill nor the appliances that white men have; and, though they can design moccasins, they can not make them properly.

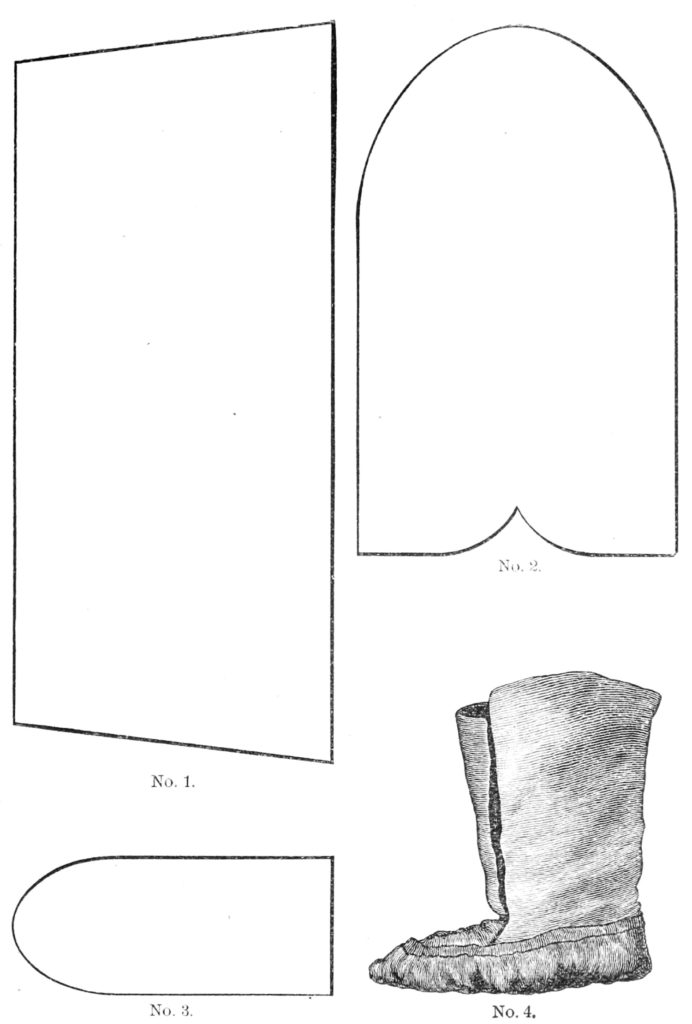

The accompanying diagram will enable any glovemaker or shoemaker to make moccasins, whether he has ever before done so or not. The feet should be made of the heaviest buckskin that can be obtained, or, better still, of elk or moose skin. The leg may be made of light buckskin, and should extend half-way to the knee.

The seams should all be sewed by hand with heavy waxed-ends. After the moccasin is completed, pierce the tongue, well down on the instep, and pass a buckskin lace, three feet in length, half-way through the tongue, in the same manner as you would begin to lace up a shoe; then pass the right-hand end of the lace through a hole in the left-hand flap of the leg, at the lower edge and well back toward the side of the ankle. Now take the left-hand end of the lace and pass it through a hole in the right-hand flap, in a position directly opposite to that on the left side. Now wrap the leg of the moccasin tightly around your ankle, outside of your trousers-leg, and taking an end of the lace in either hand, proceed to wrap it back and forth around your leg, crossing the two ends alternately in front and behind, each wrap rising above the other, until you reach the top of the moccasin-leg. Now tie your laces, and poke the ends down inside the moccasin-leg, and your feet are dressed for an all-day’s tramp.